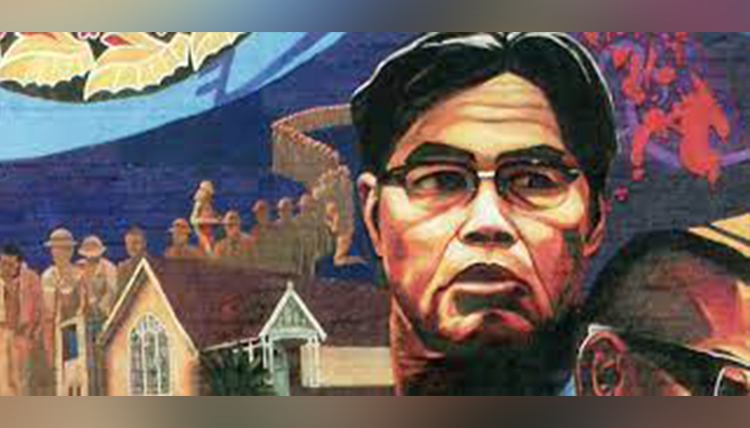

In Honor of Philip Vera Cruz (1904 – 1994)

There is a bench on "Bulldog Alley," which runs east to west, south of College Hall, that serves to remember and honor the life of Philip Vera Cruz, an influential Filipino-American leader in the organized labor movement, a civil rights activist, a founding member and vice president of the United Farm Workers union, and a former Gonzaga University student.

What Makes Vera Cruz Inspirational

Through his decades working low-wage jobs, Vera Cruz developed a philosophy that put people, especially the most marginalized, first. He believed that everyone deserved opportunities. He believed that workers needed to see each other as allies, not rivals. Also, Vera Cruz believed all workers needed labor unions because no one else could advocate as effectively for them. His collaboration with other communities serves as a beacon for future generations striving for a more equitable world.

About Philip Vera Cruz

From the U.S. colony of the Philippines, Vera Cruz migrated to the West Coast looking for opportunities in work and education.

Born in 1904 in San Juan, Ilocos Sur Province, Philippine Islands, Vera Cruz spent his youth tending to water buffalo on his family farm. Vera Cruz attended American colonial schools in the Philippines, and he dreamed of getting a college degree in the U.S., so he emigrated to Seattle in 1926. He worked a variety of low-wage jobs throughout Pacific Coast states to pay for tuition. He enrolled at Gonzaga University in the fall of 1931. As much of Vera Cruz’s income was sent back to support his family in the Philippines, he was unable to pay tuition and withdrew from school after one year. He continued doing many different jobs in hospitality, farm labor, and salmon canning, meeting working-class Americans everywhere who inspired him to join labor unions.

Vera Cruz became a labor rights activist because he and other Filipino Americans struggled to survive on farm labor wages. They went on strike in 1965.

Vera Cruz became an active leader in the labor rights movement, joining Mexican American, Black American, and other Filipino American farm workers. He co-founded the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), a predominantly Filipino labor organization headquartered in California’s Central Valley. On September 8, 1965, more than 800 Filipino American farmworkers, members of AWOC, walked out on strike against Delano-area table and wine grape growers. They protested years of poor pay and conditions. During the grape strike, farm workers demanded that grape growers pay their workers wages equal to the federal minimum wage, calling for an increase in their hourly wages from $1.25 per hour to $1.40. Farm workers merited the increase because the grape industry was booming, and they continued to meet the demanding labor needs of grape growers. Vera Cruz explained in his personal history that the Filipino laborers’ “strong labor consciousness” was due to their decades spent laboring in the U.S., and “because we listened to market reports on the radio and then discussed those reports in Ilocano, our dialect” (Scharlin and Villanueva, 40-41).

The success of the five-year grape strike relied on solidarity built between Filipino and Mexican American farm workers.

For the 1965 strike to be successful, Filipino and Mexican farm workers needed to work together. If Mexican Americans didn’t support the strike, growers would bring them in as “scabs” to replace Filipinos and break the strike. Larry Itliong, a Filipino farmworker and member of AWOC, reached out to Mexican-American farm labor leaders , César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, co-founders of the National Farmer Workers Association (NFWA), and asked them to join the Filipinos’ strike. The Filipino American AWOC and Mexican American NFWA joined together to become the United Farm Workers Union (UFW). The Delano Grape Strike grew to include 10,000 workers. Their numbers fluctuated, but they struggled, picketed, and demonstrated for five long years. By 1970, the grape strike was a complete success. At long last, Delano’s table grape growers signed their first union contracts, guaranteeing workers better pay, benefits, access to drinking water and restroom facilities in the fields, and safety protections from pesticides. This strike helped and inspired farm workers not only in California but throughout the United States.

Thus, Philip Vera Cruz’s leadership in the 1965 Delano grape workers’ strike helped set the stage for the founding of the UFW in 1967. Vera Cruz served as UFW’s vice president for 12 years. During this time, his compassion for the farmworker and the Filipino community shone. As a fierce advocate and dynamic speaker, he ensured communication with the union’s members. The UFW is the largest and longest-lasting farm labor union in the United States. The UFW has many union contracts that protect thousands of farm workers. The union has also sponsored laws and regulations that protect all farm workers in California, including those at non-union ranches.

Vera Cruz also played a key role in forming both a Farm Workers Credit Union and Delano’s Agbayani Village retirement community for aging Filipino farmworkers. Vera Cruz resigned from the UFW in 1977 but remained active in labor and social justice issues until his death in 1994 at age 89.

During his career in organized labor, Vera Cruz worked to shed light on the plight of migrant farm workers, advocating for safe working conditions, better salaries, medical care, and retirement funds. His life illustrates how we can work to create a world of collective liberation through cross-cultural solidarity.

About Gonzaga’s Vera Cruz Memorial Project

Ryan Liam (Class of 2020) was first inspired to develop a project commemorating Philip Vera Cruz after a presentation given by History Professor Ray Rast. In his Communication Studies final project, Liam, also a Filipino-American Zag, included a proposal to honor Vera Cruz on Gonzaga’s campus. Liam felt that honoring Vera Cruz on campus would be an integral step forward for the representation of Asian Americans and working-class people on campus and would help foster a more inclusive Gonzaga community that celebrates Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) leaders.

The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted Liam’s plans, but other students retained a strong desire to realize his vision. In the fall of 2021, Dr. Veta Schlimgen taught Gonzaga’s first ever Asian American and Pacific Islander History course, in which she presented the efforts of Liam to commemorate Vera Cruz, and students in the class decided to continue the movement. Inspired by Vera Cruz’s story, as well as Dr. Schlimgen’s and Liam’s proposal, Tia Moua (’23), Andrea Galvin (’26), and the Asian American Activists (a campus organization) worked to complete the project. Together, they chose this bench to acknowledge the importance of rest while fighting for justice in alignment with a core Jesuit value: Cura Personalis, care for the whole person.

The organizers included this phrase to demonstrate how meaningful change and social justice cannot occur or remain sustainable unless advocates also prioritize rest. This phrase embodies a cultural and communal aspect of self-care, reinforcing the notion that taking a moment to sit and rest together can contribute to a healthier and more connected community. As students embark on their educational journeys and put their passions into practice, they must take the time and space to care for and reconnect with themselves.

Inspired Zags

Ryan Liam, whose project inspired this memorial effort, found Vera Cruz inspirational as “a beacon of hope for the non-traditional students, first-generation college students, working-class students, students with marginalized identities.… so they [all] can see not only that they do have a place, but for whatever reason they cannot finish their education at Gonzaga, not all is lost;” they still remain part of this community.

Tia Moua added that Vera Cruz remains “a beacon of hope in so many ways….Asian students deserve to see and commemorate people who look like us. We should have more representation of people of color, especially Asian Americans, on [Gonzaga’s] campus. Our stories, our histories, and our contributions matter. His story deserves to be told and celebrated on our campus!”

Gonzaga’s Asian American Activist group explains that: In honoring Philip Vera Cruz, we recognize his commitment to social justice and the power of collective action. This memorial serves as a visible reminder of the contributions made by Asian Americans, particularly Filipino Americans, in shaping social justice movements. We designated this bench to not only honor Vera Cruz’s legacy, but also as a tribute to past, present, and future student activists who fight for social justice. In a society that forces BIPOC and other marginalized communities to fight against oppression and injustice continuously, rest is an act of resistance. We see this bench as our labor of love for current and future BIPOC students with the hope that they will feel included and represented on campus. To BIPOC communities and activists, we are here to say that it is acceptable to take up space and to rest. You have a space here, you belong here, and you matter.

It is the desire of Liam, Moua, Galvin, and other contributors to this project that Philip Vera Cruz’s story and this monument serve as a beacon of hope for non-traditional, first-generation, working-class students, and those with marginalized identities. They hope students reflect on the legacy of Vera Cruz to inspire them to mobilize in their own communities to advance justice, equity, and inclusion.