The Words Get in the Way

When you call someone a racist, that’s typically the end of the conversation.

Yes, they might actually be a racist, and calling them such might be completely accurate. But there’s no way to determine how accurate such a damning description is without taking into account several factors. And until you have the time and resources to actually assess those factors, the world could use more conversations about race, not statements that effectively end conversations before they start.

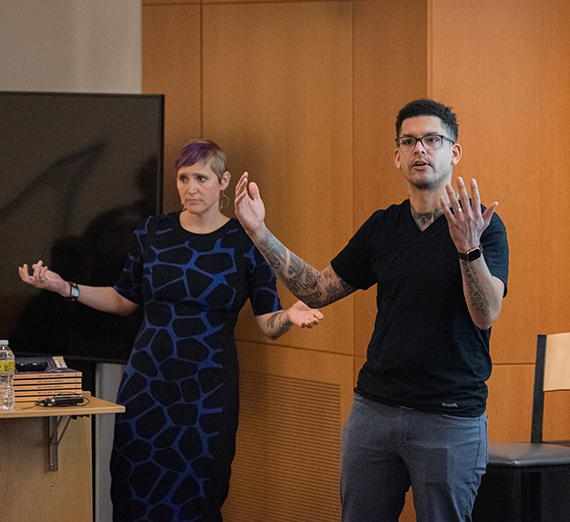

Philosophers Leland Harper and Jennifer Kling delivered the final “Leading Against Hate” speaker series presentation with a discussion of “The Language of American Racism.” Using a combination of video clips from noteworthy speakers like intersectionality expert Kimberle Crenshaw and “White Fragility” author Robin Diangelo, and their own research undertaken for their book “Racist, Not Racist, Antiracist: Language and the Dynamic Disaster of American Racism,” the duo explored several examples of racism and discussed the means to address them.

Among their examples were things like children’s Halloween costumes that misrepresent Indigenous peoples, statements by American politicians like Mitch McConnell, and news events like a Florida daycare facility dressing toddlers in blackface and a Canadian man who placed a Confederate flag and impression of a lynching in his front yard.

Kling, a professor at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs, and Harper, a professor at Siena Heights University, started with the importance of being able to recognize racism and call it out, whether it’s intentional or not. As Crenshaw said in a 2016 TEDWomen Talk: “When there’s no name for a problem, you can’t see a problem. And when you can’t see a problem, you can’t solve it.”

Seeing racist acts for what they are is the first step, they said. Whether you’re a parent forced to call your children’s school about inappropriate costumes, or a journalist who hears a racist dog whistle from a politician, silence is not an option, because silence equates to supporting the racist status quo. How one addresses the perceived racist act is the big question, they said.

Take, for example, the children’s “Indian” Halloween costume.

“Do you want to call the little girl wearing the costume a racist?” Kling asked. “Do you want to call her parents racist? Do you want to call the community racist? Do you want to call the Spirit Halloween store that sells the costume racist?”

While author Ibram X. Kendi famously puts all things in two categories, racist or antiracist, they said, Kling and Harper’s book expands on that idea by putting things on a spectrum that runs from racist to not racist to anti-racist.

In the case of the Halloween costume, it’s pretty unlikely the little girl wearing a Pocahantas costume is knowingly racist. Her parents? Perhaps they just need to be educated on what makes adopting Indigenous garb for a white person’s Halloween costume is offensive. The broader community and retail store that accepts the offensive representation might need the same lesson.

Many of the situations one encounters every day isn’t going to fit neatly into a “racist” or “not racist” bucket, Kling said. Individuals will have to determine where to draw their own line, and “you’re going to have a lot of stuff that doesn’t fall cleanly on either side of it.”

So-called “white fragility” comes in when trying to have productive discussions about race. For white people, they said, the status quo can be a pretty comfortable place to be. Anything that provokes defensiveness and a shutting down of the conversation is counter-productive to trying to address racism. And as soon as you imply someone is racist, or even just supporting a racist action, there’s a risk of the conversation ending.

“The impact of that defensiveness, however, is not fragile at all,” Kling said. “It functions as a kind of everyday white racial control by making it so difficult for people to challenge us on our unaware assumptions and biases. It functions to keep everybody in their place and protect the racial hierarchy.”

Even so, Kling and Harper said, tough conversations are necessary for American society to go forward. Not talking about it is simply not an option for anyone who truly wants to see racism minimized in society.

“Not only are we interested in most accurately describing the world, we’re interested in trying to figure out how to make the world a more just place, more equally enjoyed by all,” Kling said.

You can read our recaps of previous “Leading Against Hate” speakers Kate Bitz here, and Gina Ligon here.