Holocaust Survivor Carla Peperzak's Inspiring Story of Fighting Nazis

They had to buy their own stars.

Of all the stories that poured forth as Carla Peperzak discussed the Nazi invasion of her native Holland just as she finished high school in 1940 — stories both horrifying and inspirational — learning that the occupying Germans forced the local Jewish population to pay for the Star of David patches they were required to wear on their clothes was the kind of little detail from one of history’s darkest eras that still shocks.

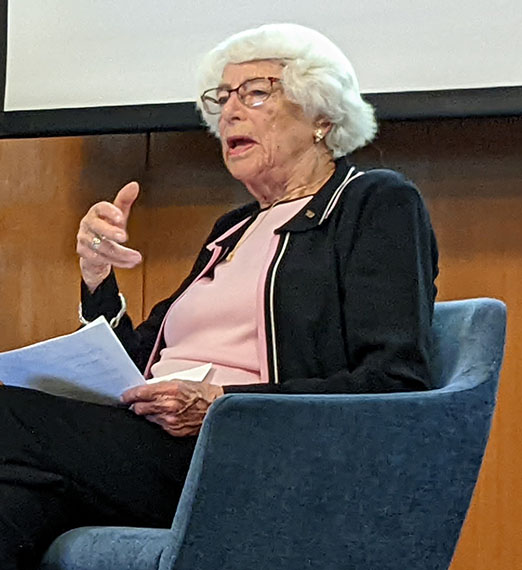

“Fifteen cents, I think,” Peperzak said as a picture of one of the stars hovered on a screen over her head in a packed Hemmingson Center ballroom Sept. 8. “You can see the dots where you had to cut around the outside.”

Peperzak, a Spokane resident since 2004, lost three-quarters of her extended family in the Holocaust. She not only survived the horrors brought on her Amsterdam community — her family attended the same Reform temple as Anne Frank, and she was friends with Anne’s sister Margot — she is a true hero. Peperzak joined the Dutch resistance as a teenager and helped dozens of fellow Jews forge ID cards or find safe haven from the German invaders and their Dutch enablers.

While the painful memories kept her from sharing her experiences for years, she now speaks regularly about hate-motivated violence of the past, and how vital it is to prevent it in the future.

Peperzak’s appearance at Gonzaga was part of the discussion “Remembering Our Past to Inform Our Future,” tied to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s traveling exhibit currently on display in the Foley Library on campus. “American and the Holocaust” remains open to the public through Oct. 7.

As a teenager, Peperzak hid fellow Jews and forged ID cards to allow the Jewish community freer access in the occupied country. Boldly, the teenager donned a German nurse’s uniform to pull people off concentration camp trains and lead them into hiding. At one point, she was interrogated by two Nazi officers who, satisfied of her legitimacy, carried her suitcase for her — a suitcase containing a fingerprinting kit and supplies for fake ID cards.

Asked by interviewer Julia Thompson of Seattle’s Holocaust Center for Humanity why she decided to put herself at risk to the Nazis at such a young age in order to help others, Peperzak casually noted that she wasn’t married with children, and only had herself to take care of, “so I was in a good position to do so.”

“I don’t think it was a conscious decision,” Peperzak said. “They asked me to help, and I could help, so I helped. I don’t think it was a decision.”

The audience heard a brief history by GU history professor Kevin O’Connor on just why the Nazis were so focused on killing Jews in Holland. Rabbi Elizabeth Goldstein, U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Washington Vanessa Waldref and former director of GU’s Center for the Study of Hate Kristine Hoover discussed what modern society can learn from the Holocaust and the forces that drove it. Associate Provost Paul Bracke hosted the proceedings.

O’Connor’s history lesson set up the context for Peperzak’s Holocaust experiences. He explained that her survival and active role in the Dutch resistance was particularly heroic given the Germans’ apparent obsession with murdering the Jews of her home country. While Jews across Europe were targeted, not all countries’ Jewish populations were targeted equally. O’Connor noted that of the 140,000 Jewish people living in the Netherlands (aka Holland) before World War II, between 107,000 and 120,000 ended up murdered by Nazis by war’s end.

As shocking as that number is, equally disturbing was O’Connor’s explanation that many of Holland’s public officials and police officers actively aided and abetted the Nazis’ gruesome extermination plan for Jews, “for the good of the state.” Of the 16,500 Dutch police officers at the time, few were active Nazis, but the vast majority helped the Nazis in rounding up Jews for the trains headed to concentration camps.

“It wasn’t hatred so much that motivated the Dutch police to arrest Jews,” O’Connor said. “It was obedience and indifference to the fate of those that were arrested, from the top to bottom of Dutch officialdom.

“The fact I’d like you to take away from my presentation is simply this: The Nazis didn’t need raving antisemites to help them carry out their mission. All they needed was people who are willing to follow orders without asking questions.”

That message echoed comments made earlier in the evening by Rabbi Elizabeth Goldstein about the current hate-fueled violence and threats that pop up locally and across the country. Noting that the “Americans and the Holocaust” exhibit asks attendees to put themselves in the shoes of Holocaust victims, she said it’s important for everyone in the community to actively confront evil as Carla Peperzak did as a teenager.

“We need to learn how to be better at reading the signs,” Goldstein said, noting that even though it can feel futile as an individual to try and counteract a seemingly large, daunting hate movement, people should know that ‘with one act, I can affect one person for the better.’”

And Peperzak is an example of how one person’s actions can affect hundreds and thousands of others for the better — not only through two decades of speaking engagements, but through her actions in Holland during the Nazi occupation. And she’s not done trying to make a difference, because preventing hate-fueled violence and another Holocaust remains vital.

“It’s so important that it doesn’t happen again,” Peperzak said.

Of all the stories that poured forth as Carla Peperzak discussed the Nazi invasion of her native Holland just as she finished high school in 1940 — stories both horrifying and inspirational — learning that the occupying Germans forced the local Jewish population to pay for the Star of David patches they were required to wear on their clothes was the kind of little detail from one of history’s darkest eras that still shocks.

“Fifteen cents, I think,” Peperzak said as a picture of one of the stars hovered on a screen over her head in a packed Hemmingson Center ballroom Sept. 8. “You can see the dots where you had to cut around the outside.”

Peperzak, a Spokane resident since 2004, lost three-quarters of her extended family in the Holocaust. She not only survived the horrors brought on her Amsterdam community — her family attended the same Reform temple as Anne Frank, and she was friends with Anne’s sister Margot — she is a true hero. Peperzak joined the Dutch resistance as a teenager and helped dozens of fellow Jews forge ID cards or find safe haven from the German invaders and their Dutch enablers.

While the painful memories kept her from sharing her experiences for years, she now speaks regularly about hate-motivated violence of the past, and how vital it is to prevent it in the future.

Peperzak’s appearance at Gonzaga was part of the discussion “Remembering Our Past to Inform Our Future,” tied to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s traveling exhibit currently on display in the Foley Library on campus. “American and the Holocaust” remains open to the public through Oct. 7.

As a teenager, Peperzak hid fellow Jews and forged ID cards to allow the Jewish community freer access in the occupied country. Boldly, the teenager donned a German nurse’s uniform to pull people off concentration camp trains and lead them into hiding. At one point, she was interrogated by two Nazi officers who, satisfied of her legitimacy, carried her suitcase for her — a suitcase containing a fingerprinting kit and supplies for fake ID cards.

Asked by interviewer Julia Thompson of Seattle’s Holocaust Center for Humanity why she decided to put herself at risk to the Nazis at such a young age in order to help others, Peperzak casually noted that she wasn’t married with children, and only had herself to take care of, “so I was in a good position to do so.”

“I don’t think it was a conscious decision,” Peperzak said. “They asked me to help, and I could help, so I helped. I don’t think it was a decision.”

The audience heard a brief history by GU history professor Kevin O’Connor on just why the Nazis were so focused on killing Jews in Holland. Rabbi Elizabeth Goldstein, U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Washington Vanessa Waldref and former director of GU’s Center for the Study of Hate Kristine Hoover discussed what modern society can learn from the Holocaust and the forces that drove it. Associate Provost Paul Bracke hosted the proceedings.

O’Connor’s history lesson set up the context for Peperzak’s Holocaust experiences. He explained that her survival and active role in the Dutch resistance was particularly heroic given the Germans’ apparent obsession with murdering the Jews of her home country. While Jews across Europe were targeted, not all countries’ Jewish populations were targeted equally. O’Connor noted that of the 140,000 Jewish people living in the Netherlands (aka Holland) before World War II, between 107,000 and 120,000 ended up murdered by Nazis by war’s end.

As shocking as that number is, equally disturbing was O’Connor’s explanation that many of Holland’s public officials and police officers actively aided and abetted the Nazis’ gruesome extermination plan for Jews, “for the good of the state.” Of the 16,500 Dutch police officers at the time, few were active Nazis, but the vast majority helped the Nazis in rounding up Jews for the trains headed to concentration camps.

“It wasn’t hatred so much that motivated the Dutch police to arrest Jews,” O’Connor said. “It was obedience and indifference to the fate of those that were arrested, from the top to bottom of Dutch officialdom.

“The fact I’d like you to take away from my presentation is simply this: The Nazis didn’t need raving antisemites to help them carry out their mission. All they needed was people who are willing to follow orders without asking questions.”

That message echoed comments made earlier in the evening by Rabbi Elizabeth Goldstein about the current hate-fueled violence and threats that pop up locally and across the country. Noting that the “Americans and the Holocaust” exhibit asks attendees to put themselves in the shoes of Holocaust victims, she said it’s important for everyone in the community to actively confront evil as Carla Peperzak did as a teenager.

“We need to learn how to be better at reading the signs,” Goldstein said, noting that even though it can feel futile as an individual to try and counteract a seemingly large, daunting hate movement, people should know that ‘with one act, I can affect one person for the better.’”

And Peperzak is an example of how one person’s actions can affect hundreds and thousands of others for the better — not only through two decades of speaking engagements, but through her actions in Holland during the Nazi occupation. And she’s not done trying to make a difference, because preventing hate-fueled violence and another Holocaust remains vital.

“It’s so important that it doesn’t happen again,” Peperzak said.

Americans and the Holocaust exhibit at Foley Library through Oct. 7