The World of My Heart

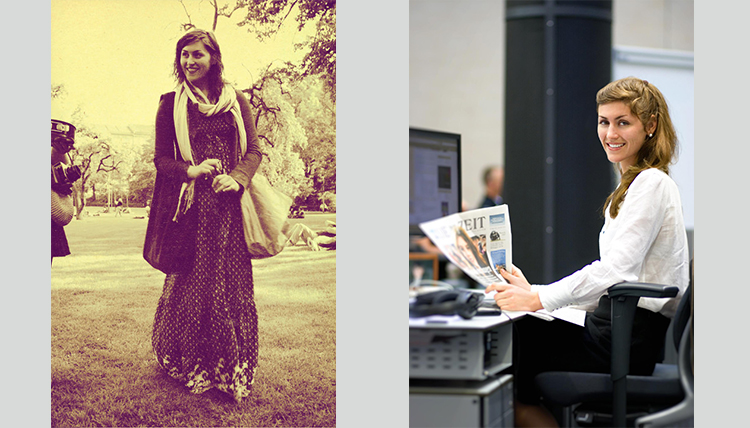

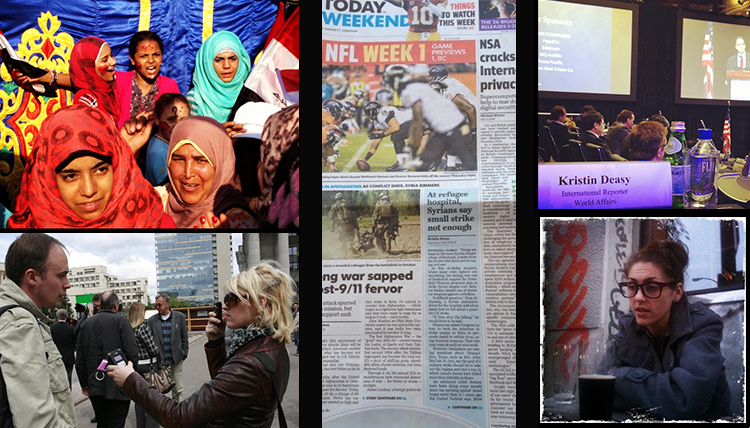

Editor’s Note: Intrepid traveler, explorer, journalist Kristin Deasy (’07) originally submitted a note to Gonzaga Magazine about finding her path in Patagonia with her partner and opening an Etsy shop to sell his handcrafted knives. But Patagonia caught my attention and after a few email exchanges, Kristin agreed to pen a travelogue for Gonzaga readers. Are we seeing the first stab at a memoir? I’ll let you be the judge of that.

This is the extended version of Kristin's piece in our a three-part journalism feature from the Summer 2022 issue of Gonzaga Magazine. Other pieces include "Turning the Tables" - featuring several former Bulletin writers - and "Shedding the Same Tears" - a reflection by Eli Francovich ('15) on reporting from the warzone at the Ukraine border.

2007: Graduated from Gonzaga

Gonzaga formed me in many ways. Journalism, philosophy and music – my major and minors, respectively – went on to become the cornerstones of my adult life.

In my freshman and sophomore years, my friends were largely intellectual upperclassmen and women, so I too styled myself an intellectual. It wasn’t true, though. I tried to talk the talk, but I never really walked the walk. The real world, with all its inexplicable pain and glory, captivated me far more than the books and theories of the lecture hall. I was also too much of a dreamer, which is what initially got me into philosophy – until it hit an analytical dead and left me a mystic.

I was, however, a pragmatic mystic. This may sound like a paradox, but as Fr. Spitzer often pointed out in his evening philosophy courses that I audited at Gonzaga, quantum physics bridges that gap quite nicely.

But by the time I hit my senior year, having done the rounds as student senator, yearbook editor, church cantor, editor-in-chief and designer of an alternative campus student magazine, founder of a campus-based support group for the local women’s homeless shelter, and vocalist in the Coeur d’Alene production of Verdi’s La Traviata, I was done.

I had major senioritis. I was ready to fly the nest … at the time, I never imagined I’d fly so far.

2007-2008: Washington DC, intern at USA Today

Life quickly swept me up and installed me in a small, bright orange room in a rowhouse just off Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C.

Monday through Friday, I took the metro into Virginia and got on a bus that left me standing in front of USA Today’s looming, multi-story main headquarters. I was showed into the paper’s editorial offices and introduced me to my new boss – I was on a year-long fellowship – the head of the Opinion section. My job? Fact-check. Fact check every famous person who submitted a column considered potentially worthy of publication. Can’t find the source? Maybe it was pulled out of thin air – call the writer. ‘Yes, call the writer! We don’t care how famous he or she is, they need to get their facts straight if we’re going to publish this thing.’ Well. That became my life.

My analytical mind sharpened. I began to see how information is used, both in media and in argument. I started to notice not just when a fact was wrong, but when it was taken out of context or cherry picked. I learned to deal with big egos that didn’t like being confronted by a 22-year-old fact-checker. I also participated in editorial meetings and had to vote on the controversial political issues of the day (Obama was then campaigning for president), aware that my decision could swing the paper’s entire editorial position. It was a lot of responsibility, and a lot of information.

In need of money to keep paying my student loans and subsidize voice lessons, I waitressed at a flashy microbrewery in Tyson’s Corner at nights, where I often ended up entangled in complex political discussions with diners.

Once, the editorial department went to D.C. to visit Hillary Clinton, which surprisingly wouldn’t be the last time I would see her. Another time, Joe Biden, then a mere senator, came into the office to try and gain editorial support on an issue. One thing he said has stuck with me through the years. Geopolitics, he remarked, grinning – he did a lot of grinning -- is like family. International relations are no different from family relations. Once you understand that basic mechanism, you understand everything.

Little did I know, I was about to experience that first-hand.

Sept 2008: Moved to Prague, Czech Republic

As a child, I loved adventure stories. Once I asked my mother if adventures were real, or if they only happened in books. Life took it upon itself to answer, and soon swept me overseas for another year-long journalism fellowship, this time in Prague, Czech Republic.

I still remember the feeling I got when I first landed in Prague. It is different, the feeling you get when your plane lands in a country to live rather than visit, particularly if you’ve never been there before. Visiting, Prague is charming and dainty, like a fine piece of porcelain. Everyone gushes over it. It’s so exquisite and so old. To live in it is more akin to being hit with a dead weight. As I took my first steps in the city’s centuries-old cobble-stone streets, my initial impression was one of heaviness. A heaviness in the people, in the buildings. There is an ancient, strong sort of darkness lying at the core of that place. The feeling grew as I neared my new workplace, an imposing, large black mass at the top of Wenceslas Square, which I soon learned was the ex-communist headquarters.

I squared my shoulders and headed for the front entrance, which was ringed by beefy security guards speaking gruffly in Czech. My new position saw me in the newsroom of Radio Free Europe/Radio Free Liberty, a US-funded organization dedicated to supporting a free press in countries around the world. My work life soon became deeply international as I was sent off to answer questions or glean information from one of the building’s many bureaus, consulting Kazakhs, Iranis, Georgians, Turkmen, Iraqis, Uzbeks, Pakistanis … the list goes on.

My formation as a journalist truly began here and is largely thanks to two people, a Romanian and if I remember correctly, a Bosnian, who patiently informed me, time and time again, that my news briefs were not up to scratch. Coming from the flowery, overstated world of opinion and commentary, news writing was like a foreign tongue. My task consisted of condensing a breaking news item into a short, easily translatable paragraph for use in radio broadcasts in multiple languages.

The nature of the work put me under constant pressure, as I needed to publish timely short pieces that communicated complex language and events in a simplified form better suited to immediate on-air translation in numerous languages. This did not come easily to me. I remember grumbling about my ‘overseers’ to friends over frothy beers after work. What my twenty-something ego couldn’t see then, I can see now: it is thanks to them that I became a journalist at all. Later, I began writing and reporting in earnest, doing long-form investigations on various geopolitical issues, many of which came to my attention through my friendships in various bureaus.

My friends were Irani, Iraqi, Pakistani, Czech, Bosnian, Ukrainian, Serbian … and with many of them, I partied--and we partied hard. Prague is the party capital of Europe and I soon saw its rough underbelly. I ran with a crowd that loved art, film and a serious nightlife. I fell in love with an Irani coworker. Philosophically, I was immersed in nihilistic Europe and questioning everything. Musically, I was still cantoring in a local church because I knew, in my heart, that losing music would mean losing a part of my soul. But I didn’t have any confidence in myself as a musician and the threads binding me to organized religion were growing thin. I learned complex musical pieces by ear – Bach, Mozart, et al – but I had no idea how to make sense of a written sheet of music. Gonzaga left me heavily in debt and I asked myself how I could possibly make ends meet as a singer. Meanwhile, I was falling under the spell of the promise of a glittering career in international journalism. While reporting didn’t pay much, my career seemed to be unrolling by itself, as if by magic.

Then suddenly, one Sunday, someone heard me cantor in church and told me I needed to study with an Italian maestro of the bel canto style, who would soon be in Prague to give a masterclass. It felt like a scene out of a movie. This is my big breakthrough, I thought. I’ll be discovered! My dreams will all come true! My heart leaped. I joined the masterclass and began regular study with my new maestro.

What I didn’t understand – or didn’t want to understand – is what it would really mean to follow my heart. To become a professional musician signified an investment in time and energy that I wasn’t prepared to make at that time.

I was being pulled two different directions, like a tug-of-war. Journalism was yanking hard, its weight heavy with the desire to defend human rights and fueled by a rather innocent belief in the idea of a ‘free’ press. Meanwhile, the constant partying and a troubled relationship with my new boyfriend was fraying the ropes.

Conditioned by Western culture to establish self-worth through external achievement, I proceeded to work harder and traveled throughout Europe, visiting Italy, France, Spain, Lithuania, Poland, Turkey, the Balkans and even Iceland, among other places. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty hired me, and I became a junior correspondent. Hillary Clinton visited (hello again). The more I worked, the thinner I became, until I looked, in the words of my boss, like a “Modigliani portrait.”

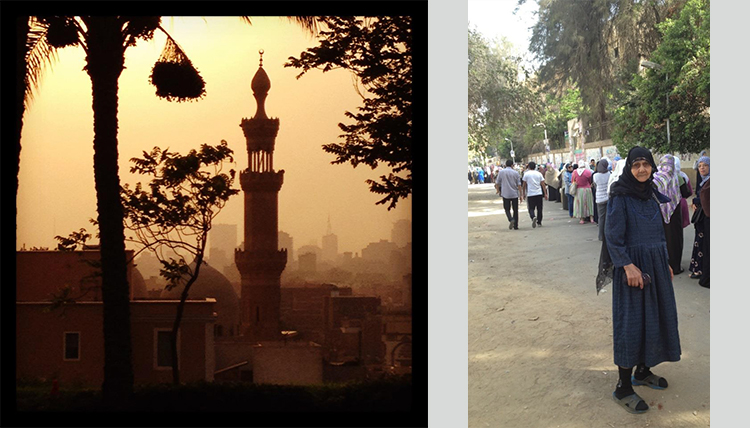

2011: In Cairo, Egypt

If you are familiar with the Modigliani paintings, picture one of a wan, dark haired woman with penetrating brown eyes. Now, just for fun, add an Islamic headscarf. The Islamic call to prayer sounds in the background. Dust floats up from a corner of the painting. Clearly, we’re a long way from Modigliani’s stomping grounds.

Smoke from the exhalation of a nearby ‘shisha’ or waterpipe is drowned in a flurry of Arabic. If you listen closely, you can hear water – that’s the Nile, lapping languorously along. Welcome to Egypt. My first visit to this great land was a short, 10-day stint as an invited fellow for the 'Covering a Revolution' event that brought together 17 young journalists – 8 Americans, 9 Egyptians – to cover aspects of the Egyptian uprising. At the time, Egypt was in major societal and political upheaval – an extension of the Arab Spring uprisings.

Unlike many of my fellow budding young US journalists, I’d come from a deeply religious home and practiced faithfully for many years. As a result, I immediately understood other young Muslims. I knew where they were coming from. In fact, I felt right at home in Egypt. From the moment I arrived, I felt like I’d lived there my whole life.

Of course, on one level, I understood I was a foreigner and there was much I didn’t understand – most importantly, the language – but on a gut level, I ‘got’ Egypt in a way I’d never gotten the Czech Republic. And I loved it. I loved everything about the country: the inscrutability of the people, their easy laughter, their satiric approach to society.

There was something about this very ancient land – where you could still sense a thin, golden thread binding it to a time of deep wisdom and wonder – and the way it shouldered the confusion and stark poverty of a modern-day nation struggling to understand itself and its role in a changing world. Something beautiful.

I made friends easily with young Egyptians and other Arab countries. I rode a camel around the Pyramids, and naturally I agonized over the article I was asked to submit (we all wrote one) – a profile of a young Egyptian woman who said she was subjected to 'virginity testing' while detained by the military. In short, I had the time of my life. I didn’t want to leave and said goodbye reluctantly, sensing – correctly – that it would not be the last time I set foot in that great land.

Christmas 2012 - August 2013: In the U.S.

Here is where we enter the ‘dark night of the soul’ part of the story. My relationship with my boyfriend disintegrated spectacularly. I purposefully sabotaged my future at Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty by informing my boss what I really wanted was to become a professional singer. When it became clear to me that the foreign bureaus used little of the English-language newsroom’s radio scripts – thanks largely to the rise of tools like Google Translate – I moved to Berlin, looking for a fresh start. But the nihilism I’d carelessly adopted in Europe, combined with serious questioning about the purposefulness of my career and my inability to pursue music more seriously, began to eat away at me.

My wan, Modigliani look gave way to an emaciated, Holocaust-survivor look. Anorexia took center stage of my life. I flew home for Christmas and was unable to return after seeing a doctor for what I thought would be a routine physical where I was told flying would endanger my life due to my extremely low weight. I was told to check into a treatment center where I’d be charged thousands of dollars (money I didn’t have) and forcibly fed thousands of calories per day. The relapse rate? High. There had to be some other way.

In a stroke of luck – or grace – I received a scholarship from my hometown’s eating disorder fund and started working with a therapist. I have spent the last 10 years unraveling this long dark night of a soul, which held sway over my life in greater or lesser degree for nearly as many years (amenorrhea for seven of them).

So, what happened? This is the question everyone asks. What makes a body stop feeding itself? The mechanics of eating disorders are better understood today, but the cause is not. Numerous factors favor its development, among them genetics, a so-called ‘hyper-sensitive’ personality, cultural conditioning, ingrained misogyny, abusive relationships and the way messaging is received and interpreted in childhood. In my life, many of those conditions were there: recognizing that I was a particularly sensitive child, my parents pulled me out of school when I was young and brought me up isolated from society in a tightly religious homeschool environment where I was restricted to 1940s-1960s entertainment with all the values of the period (the hourglass figure, the perfect wife, Leave It To Beaver etc).

Unable to develop among my peers, I placed great importance on what I gleaned from television, and later, the internet. The importance of being thin and beautiful for acceptance and success in society impressed itself deeply upon my psyche. Meanwhile, as was the case in many households during the processed-food frenzy of the ‘90s, emotional eating was normalized. Food became a way to deal with emotions, and mine were out of control.

Later, I became enamored with a man who made it clear he favored the thin, sexy women featured in film and media, leaving me at odds with my average, healthy weight and cankles. Finally, I had long since left my religion and was philosophically unmoored.

I was primed, and the killer advanced. And who was the killer? Not my parents, not society, not the full-length mirror, not that one guy who said that one thing, but my own thoughts. Yes. I believed my thoughts with the fervor of a religious fanatic, and these thoughts – empowered by my complete and total identification with them – gained momentum.

All great religious and philosophical texts discuss the phenomenon of thought: it lies at the heart of what it means to be human. Do I think, and therefore I am? Or do I think, and therefore I am not … at least not literally that thought, given that I have the power to recognize it? The very fact that we have the capacity to observe a thought undercuts the idea that our thoughts are somehow who we are, but modern history has been a lesson in unlearning this simple fact.

We often don’t even think twice about it: “Of course that’s me, I’m thinking it! I’m right! I have all the proof!” Therein lies the cause of all war and all human suffering – anorexia included. If we were 100% what we think, we wouldn’t even be aware of the thinking process. And if our thinking aligned 100% with who we really are – if one can even put a word to that (which one can’t; it goes beyond the duality of language), the closest approximation would be Love – perhaps we would not suffer. One possible way of looking at suffering is that it is the natural consequence of believing things that go against our nature, even things as mundane as “my husband’s a jerk for not doing the dishes.”

Quite frankly, it wasn’t until I arrived at that point – the mundane, the every-day thoughts – that I truly began to squeeze out from under the tight grip of anorexia. Recovery truly started when I began to disidentify from them and open to a place of observing.

However, given the deep grooves in my neural pathways from so many years of militantly believing my thoughts, particularly around food and body, this ‘waking up’ process was slow, and I was, for a long time, terrified of it. The reason for this might not be immediately obvious. Those thoughts and the images accompanying them: If I eat this, then … [insert image] were awful little mental eddies, but at least they were familiar. Painfully familiar, but familiar.

Who would I be without those thoughts? That was a question I was too terrified to consider for many years. It was new. It was scary. It was like choosing to trigger a devastating earthquake in my internal world, and I had no idea what would be left of me after, if anything. Thus, in the immediate years I pushed it all away in the classic American way: by throwing myself into work. And how does an international journalist throw herself into work? By entering a war zone, of course.

Fall 2013: In Reyhanli, Turkey, entered Syria

The hardest thing I’ve done in my life was not cross into a part of Syria recently taken over by ISIS and under imminent threat of US bombardment. It was actually a very simple thing, one I had done dozens of times: boarding a plane.

Getting on a plane in San Francisco, destination Europe, still thin but medically ‘stable’, was the single most difficult thing I have ever done. Leaving my comfort zone, leaving the economic security of living with my parents, leaving my therapists, leaving it all and going back on my own terrified me.

Even so, my instincts told me it was the only way out. I was spinning in circles in my childhood home. With each day that passed, it was getting harder to believe myself strong enough to leave. So I bought the ticket and said goodbye to my family. I let myself break down when I’d made it to the gate. In that moment the pain was so powerful it tore through me, a raw, immobilizing torrent of grief. People looked at me like a was a lunatic or someone who needed medical help. A total stranger gave me a chocolate bar, a bottle of water, and some kind words about how that always makes his wife feel better.

I looked at the chocolate bar and immediately doubted I’d eat it (I did – in tiny bites over a period of months). Then I was off – and I knew I was off to Syria. I had already decided.

I was nearing 30, I had courted death, and I was clear: I needed to say goodbye to journalism and dedicate my life to music. I couldn’t say goodbye to journalism from where I was standing, however. I had written literally thousands of news stories over the years, much of it breaking news on the Middle East. I knew what was going on in Syria, and that knowledge came with responsibility. I had the tools and the opportunity to bring more awareness to what not just what was happening there, but what Syrians themselves were experiencing.

I knew I would never be at peace with myself if I didn’t try – yes, even if it killed me. I was still sick enough to not really care about death, so it wasn’t heroic of me. Absolutely not. At that point, it didn’t make much different to me whether I lived or died.

I returned to Europe, immediately flew to Turkey for a Syrian conference on restructuring civil society, made contacts, and went to the border. At this point – fall 2013 – Obama was on the point of firing missiles into the area and all movement was strictly forbidden, even humanitarian. US freelance journalists were strictly prohibited from entering Syria over fears of kidnapping: White House orders.

Undeterred, I donned an Arabic disguise and convinced a humanitarian group to take me with them to the nearby Atmeh refugee camp in Syria, home to some 22,000 and the largest refugee camp in the country. My points of contact were overwhelmingly among the opposition, though I did occasionally speak with Assad supporters. I was always eager to hear all sides.

I met and spoke with Syrians of all ages and heard countless gory, utterly dehumanizing, heart-wrenching stories. I published a front-page news story for USA Today based on interviews at the local border hospital.

When I was leaving Atmeh, children – presumably orphans – ran behind us, begging us to take them with us. I stopped in my tracks. Turning around, I looked at one of the little girls for a few moments and our eyes met. Then, impulsively, I ran up to her and hugged her to me fiercely. I lost all concept of where I was while in the embrace of this small Syrian child. I was unable to take her with me that day, but I have carried her with me in my heart ever since.

At the time, however, I had to come back to reality swiftly, as we had problems. Major problems. A man commanding a Turkish border tank had approached us and was giving us trouble, demanding passports, making threats, likely seeking sex as payment. All he got was so much hysteria (mostly mine) that he finally relented and let us pass. If things had gone differently, I’d probably still be rotting in a Turkish prison somewhere, or worse. But life was not through with me yet…

2014: Moved to Buenos Aires

Right before I moved to Berlin, I bought a ticket to Buenos Aires, Argentina. It was a cheap ticket about a year out, so I bought it.

‘I’ll just visit Argentina on my way back to California for Christmas,’ I thought, but what I really meant by that was: ‘I think I might need to move to Argentina.’

I was done with Europe. It’s been nearly eight years now since I’ve moved, and really the only thing I miss are the fresh-baked croissants from European corner shops. That first visit to Buenos Aires left me in a daze.

I had become so used to the reserve and distance of Eastern Europe and Germany – which I actually consider very honest and rather upstanding – that the loquacious amiability of Argentina, with its constant hugging, smiling and helping, quite literally gave me culture shock.

I walked down streets filled with tango music and the fragrance of blooming purple jacaranda trees. People were purposefully kind. I was incredulous. The city was beautiful and filled with parks. I told the family friend I was visiting about my desire to study music. Why not study here? he asked, and the pieces began to fall into place. I somehow managed to audition to the largest music conservatory with half-remembered bits of high school Spanish, and felt my whole world shift when I opened their acceptance letter on Christmas Eve in California. I was moving to South America!

Once installed in Buenos Aires, I began the long process of integration. I already knew what it was like to live abroad in an English-speaking expat bubble – I had done so in Prague – and it wasn’t enough for me this time around. I wanted to know these people, to speak their language, to get deep inside this culture. To fully integrate.

Like Egypt, Argentina was immediately understandable to me. It is a heart-based culture, one of few left in the world. The society is fundamentally inclusive and family-based, with all the intricacies and paradoxes of a real family: it’s warm, funny, often insincere, sardonic, kinda weird, tolerant, corrupt, kind, dysfunctional, nostalgic, occasionally passive-aggressive, fatalistic yet unfailingly loving.

It was in Argentina that I recovered the voice I’d lost to illness and poor teaching. It was in Argentina that I discovered the depths of my own heart. It was in Argentina that I healed my body and experienced the joy of movement and dance. It was in Argentina that I formed myself as a musician. It was in Argentina that I found true love. This country has become my home.

Summer 2017: First summer in Patagonia – the power of Nature

My third year into music conservatory, I left the city for the summer to volunteer at a farm in Patagonia. I knew next to nothing about farming, but I told the woman seeking volunteers—also an expat, also a journalist – that I was a quick learner.

I soon installed myself in a tent on the top of a little mountain in a rural area just outside the popular mountaineering town of El Bolsón. I lived in the tent for several months and showered maybe once a month. I weeded the garden, befriended my boss, and became the farm chef – where I first learned how to cook with fire in extremely rustic conditions.

I’d spent the last several decades of my life in major cities: DC, Prague, Berlin, Cairo, even a short stint in New York City. I associated camping with vacations. But summer break in Argentina is nearly four months long, and with time my body started to experience living close to nature as a veritable way of life rather than a temporary affair. I settled in. I began to notice how happy I was. I started singing in nature, improvising, opening to a conversation between music, nature, the birds, the mountains, and the voice.

During my years in conservatory, I sang and performed the principal soprano role in one of Mozart’s operettas, I’d sung jazz on stage and even recorded some Argentine folklore songs, but none of them felt right for me. Patagonia became my muse. By the end of that first summer, I knew I’d come back for more. And by the end of the second summer at the same farm – punctuated by a trip across the Andes on horseback in similarly rustic conditions – I knew I needed to live in nature. And not just any nature: this nature, these mountains, this part of Patagonia.

My recovery from anorexia was coming full circle and I was finally feeling open to a relationship again after nearly seven years single. I started to let myself dream a little about the ideal person for me…and then one day, while watching the farm for my friend while she was gone, there he was, standing at the door, a bottle of Malbec hanging from his bag. “Hola,” he said, rather shyly. I knew he was an artisan; we had met briefly once. “I was told I could come by and look for some wood.” His search turned into the find of our lives: one another.

Now: Mallin Ahogado, Rio Negro, Patagonia

Today, we live in a little cabin nestled in the foothills of the Andes accompanied by two grey cats. Our story isn’t much different from that of many others: we’re slowly saving up money to buy our own little piece of land, build a house, and enjoy a modest homestead.

I launched an Etsy store to support my partner’s amazing craftsmanship and spend my days singing and composing – I will be releasing my first single soon. In my free time, I play the lyre, cook, garden, make flower wines and teach my neighbors' kids English.

My initial transition to rural life was rough, living first in a shack that didn’t have all four walls (it snows here in the winter), no electricity and no running water, then running a mountain refuge that at least had four walls and running water but was otherwise extremely rustic, and finally renting this little cabin that covers the basic necessities and even has internet!

In the interim I’ve learned how to chop wood, purify water, cook and heat a home with only a wood-burning stove, store for the winter, gather local medicinal plants and adjust to the many (different) social mores that come with rural life in Argentina.

I finally have a handle on the basics, but sometimes I still do crazy things no one would do around here, like take a lamb with a broken leg to sleep with me to bed to make sure she stays warm and heals well, which she did.

After all, one thing Argentina has taught me is this: If you can help, do so. We’re all in this together.

- Academics

- Alumni

- Careers & Outcomes

- Global Impact

- College of Arts & Sciences

- Alumni

- Academic Vice President

- Journalism

- Gonzaga Magazine