On Useful Tools: Buffalo Bill, Women's Suffrage, and the Value of Unexpected Advocacy

An intersection of my research and the Women’s Suffrage movement leads me to a lesson about the value of unexpected advocacy.

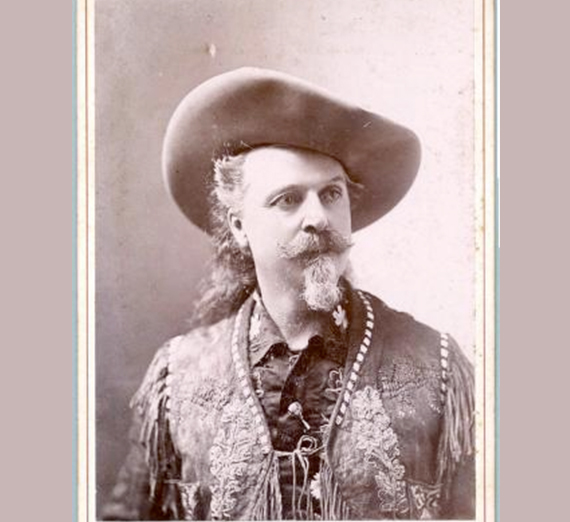

Years ago, I was researching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a traveling show that crisscrossed the U.S. and Europe from 1883 to 1913, celebrating the “Frontier Myth” of Euro-American conquest. Led by William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, the show had hundreds of thousands of viewers. It valorized masculinity and militarism in a macho spectacle.

And, so, when leafing through archived pamphlets, I groaned at a heading in the 1899 season’s playbill entitled, “Colonel Cody on the Sex Problem.” Given Cody’s hyper-masculine persona, I cringed to think what the “sex problem” might be. What followed surprised me.

Responding to the question, Do you believe that women should have the same liberty and privileges that men have?, Cody was quoted: “Most assuredly I do. I've already said that they should be allowed to vote.” He went on to defend the rights of women to live, work, and profit for themselves, to deride criticism of women’s financial and ideological independence, and to explicitly endorse equal pay for equal work.

It was a startling find that defied my expectations, in part because Cody did not need to publish his position. But he did. He had a uniquely prominent platform to advocate for a cause, and he used it.

The incident speaks to a phenomenon I see in the classroom and broader society today. It speaks to those students and others who avoid uncomfortable discussions and campaigns for justice at least in part because the injustices at hand do not affect them directly. For those who benefit from a system, it can be tempting to stay silent, even when it’s clear the system oppresses others around them.

Having the choice of whether to engage, though, is a privilege. And privilege is leverage. People may use their privilege – with access to money, influence, or prominent platforms – for or against a cause. But those who are silent also use privilege as leverage; they rest a weight upon the shifting scales of public opinion and, by not choosing a side, they support the status quo.

I frequently see members of my own community hesitating to get involved in issues where they are not inherently at risk: white students hesitating to march in support of Black Lives; citizens hesitating to defend the dignity of immigrants and refugees; straight cisgender colleagues hesitating to support LGBTQ+ causes; or family members failing to object when another says something bigoted. But as Linda Alcoff notes, even if such hesitation is motivated by a desire to avoid “speaking for others,” retreating from public engagement and vocal support is also damaging. Every cause needs advocates and allies.

William Cody was bombastic and masculinist. His support of women, even in the program quoted above, was often paternalistic. He celebrated wars of aggression against Indigenous Americans and helped drive the American Bison to near extinction. He was most certainly a tool, to speak colloquially. But for this one moment, for the cause of Women’s Suffrage, he was a useful one.

Men like Cody are rightly not the first people mentioned when celebrating Women’s Suffrage campaigns. Yet involvement of men like Cody remains a useful lesson – especially at a time when social media grant everyday access to audiences beyond Cody’s wildest dreams:

If you have a platform that can help a cause for justice and dignity, you should use it. If you see a group struggling, link arms with them in solidarity. If you have privilege, don’t let your inaction be your contribution.

It matters when an unexpected but influential person – like, say, John Cena or Taylor Swift or Steph Curry – speaks out in support of a group to which they do not belong. They use their position to push the conversation among audiences that may otherwise disengage, ignore, or simply never hear it.

Advocates for any cause can and always should be ready to step aside, hand over the microphone, and embrace the opportunity to learn more, with humility. I doubt “Buffalo Bill” was willing to take that step. But engagement is better than disengagement or silence. The world needs more useful tools and fewer obstinate blowhards.

Photo source: https://www.biography.com/performer/buffalo-bill-cody

Years ago, I was researching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, a traveling show that crisscrossed the U.S. and Europe from 1883 to 1913, celebrating the “Frontier Myth” of Euro-American conquest. Led by William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, the show had hundreds of thousands of viewers. It valorized masculinity and militarism in a macho spectacle.

And, so, when leafing through archived pamphlets, I groaned at a heading in the 1899 season’s playbill entitled, “Colonel Cody on the Sex Problem.” Given Cody’s hyper-masculine persona, I cringed to think what the “sex problem” might be. What followed surprised me.

Responding to the question, Do you believe that women should have the same liberty and privileges that men have?, Cody was quoted: “Most assuredly I do. I've already said that they should be allowed to vote.” He went on to defend the rights of women to live, work, and profit for themselves, to deride criticism of women’s financial and ideological independence, and to explicitly endorse equal pay for equal work.

It was a startling find that defied my expectations, in part because Cody did not need to publish his position. But he did. He had a uniquely prominent platform to advocate for a cause, and he used it.

The incident speaks to a phenomenon I see in the classroom and broader society today. It speaks to those students and others who avoid uncomfortable discussions and campaigns for justice at least in part because the injustices at hand do not affect them directly. For those who benefit from a system, it can be tempting to stay silent, even when it’s clear the system oppresses others around them.

Having the choice of whether to engage, though, is a privilege. And privilege is leverage. People may use their privilege – with access to money, influence, or prominent platforms – for or against a cause. But those who are silent also use privilege as leverage; they rest a weight upon the shifting scales of public opinion and, by not choosing a side, they support the status quo.

I frequently see members of my own community hesitating to get involved in issues where they are not inherently at risk: white students hesitating to march in support of Black Lives; citizens hesitating to defend the dignity of immigrants and refugees; straight cisgender colleagues hesitating to support LGBTQ+ causes; or family members failing to object when another says something bigoted. But as Linda Alcoff notes, even if such hesitation is motivated by a desire to avoid “speaking for others,” retreating from public engagement and vocal support is also damaging. Every cause needs advocates and allies.

William Cody was bombastic and masculinist. His support of women, even in the program quoted above, was often paternalistic. He celebrated wars of aggression against Indigenous Americans and helped drive the American Bison to near extinction. He was most certainly a tool, to speak colloquially. But for this one moment, for the cause of Women’s Suffrage, he was a useful one.

Men like Cody are rightly not the first people mentioned when celebrating Women’s Suffrage campaigns. Yet involvement of men like Cody remains a useful lesson – especially at a time when social media grant everyday access to audiences beyond Cody’s wildest dreams:

If you have a platform that can help a cause for justice and dignity, you should use it. If you see a group struggling, link arms with them in solidarity. If you have privilege, don’t let your inaction be your contribution.

It matters when an unexpected but influential person – like, say, John Cena or Taylor Swift or Steph Curry – speaks out in support of a group to which they do not belong. They use their position to push the conversation among audiences that may otherwise disengage, ignore, or simply never hear it.

Advocates for any cause can and always should be ready to step aside, hand over the microphone, and embrace the opportunity to learn more, with humility. I doubt “Buffalo Bill” was willing to take that step. But engagement is better than disengagement or silence. The world needs more useful tools and fewer obstinate blowhards.

Photo source: https://www.biography.com/performer/buffalo-bill-cody