Experiential Learning Examples: Bridging Gaps at the Borders

Building relationships with those who are most impacted by systems of injustice helps us to put aside fear and to be part of positive change. This kind of learning takes place outside the classroom, in places where students become comfortable with bridging gaps in our communities

January 2019 marked my third trip to the U.S.-Mexico border with Gonzaga undergraduates during an immersive learning opportunity called Justice in January. I’m a sociologist, but not one who is a specialist in immigration, or the history of the border. However, I was excited because it seemed like an incredible opportunity to accompany students in an experience focused on a topic that is vitally important.

The first year I went on the trip (2017), I had a very clear goal: Write down every question, or key issue about immigration, the border, etc., that students talked about over the course of the week. The purpose was to create a “Justice in January class” for students going on future trips. Over the next several months, I took those notes, collaborated with a colleague who is an immigration expert, and created an 8-week mini-class for all students going. I also partnered with Darcy Phillips, the service immersion program manager for the Center for Community Engagement, who has expertise accompanying students to a wide variety of settings.

The 8-week course provides an overview of the current immigration system in the U.S., some historical background on the border and the rise of border enforcement, and how (and why) Americans have thought what they’ve thought about immigration across the southern border over time. While the content of the course is important – to provide a common baseline of information for students to enrich their Justice in January trip experience – the more important function of the class is community building.

The class allows for a structured, regular space to get to know each other and to engage in conversations about immigration and border-related issues. From my perspective, building relationships and learning how to talk about immigration is foundational for the trip to truly be successful.

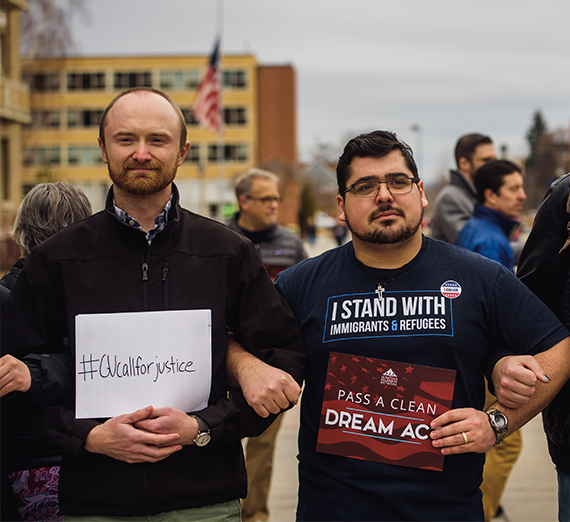

Johnston, center of back row, with participants of the 2019 Justice in January trip to the US-Mexico Border.

Patterns of Racial & Socioeconomic Segregation

The course, and the trip, are also fascinating to me because of my own research interests around understanding urban inequalities in K-12 public schools in the United States. In particular, I’m interested in how patterns of racial and socioeconomic segregation (or integration) in our communities shape the way parents/guardians perceive what constitute “good” and “bad” schools. These perceptions about schools are important for understanding how urban educational policies – charter schools, integration plans, school finance reform – come to be adopted, or not.

Understanding how more integrated, just communities and schools are possible is central to my scholarly identity, and aligns with the mission of Gonzaga University. In particular, I connect closely with the goal of “fostering a mature commitment to dignity of the human person, social justice, diversity, intercultural competence [and] solidarity with the poor and vulnerable.”

I see so many parallels between the perceptions of urban public schools in the U.S., and how negative perceptions manifest themselves about migrants across our southern border. In each case segregation – living and socializing in communities that are racially and socioeconomically homogenous – allow for stereotypes about “others” to manifest themselves. The Justice in January immersion trip is an opportunity for Gonzaga students to interact with a range of individuals and organizations, in the U.S. and Mexico, ask critical questions, and reflect on their prior perceptions about immigration.

This kind of immersive experience has the capacity to shape the life course of our students as they embark on a lifetime, which hopefully is concentrated upon living with and for others in service of the common good.

What I love more than anything else about Justice in January is that I get to “simply be” with students for a week. I love going on evening walks with the students to process and reflect on the day. I am regularly impressed by listening to the connections they identify.

The Walking School Bus

I formerly taught in the Indianapolis Public School district – specifically at the same school my grandmother had attended 70 years earlier. When my parents heard that this school and others in the area were going downhill, they moved so that I would attend another school – in a “good” neighborhood.

When I worked in that district, I never had many interactions with those “bad” neighborhoods – I just drove through them from time to time on the way into downtown Indianapolis.

Today, I participate in The Walking School Bus along with students in several of my classes. This program encourages community members to walk to school with young children whose homes are too close to the school to ride the bus. The purpose is not just safety, but also a closer connection between residents of any given neighborhood.

The greater value in something as simple as walking children to school is developing relationships, because those relationships replace wide-ranging stereotypes about entire neighborhoods in our Spokane community. Eventually, students look around and ask the question, “What the hell is everyone so scared of?”

Just like the boundary line at our national border, there are boundary lines in our communities based on fear manifested from a lack of information and engagement with people. The hope in immersive learning opportunities – whether in our local communities or further away – is that we are building relationships with those who are most affected by systems of inequality.

If we are truly dedicated to serving the common good, then we must be intentional in understanding how our humanity is inextricably tied to the humanity of every other person. Because, as Kent Hoffman reminds us, “Every person has infinite worth.”

Email the author: Joe Johnston