Mountains of Metaphors

Lessons in Leadership Amid Crisis

Photos by Kyle Denton (’18)

A SITUATIONAL ASSESSMENT

To reconnect alumni in adventure-based leadership development and practice.

“Dare to Lead” (Brene Brown) and “Peak Performance” (Brad Stulberg and Steve Magness) informed the planning and execution in a high-stakes alpine environment.

Ascend and descend the mountain in three days, with nightly debriefs and reflections.

Mount Whitney (California), the tallest mountain in the lower 48 states; 14,487 ft. above sea level.

Veteran mountaineers and novice climbers, all briefed for such an adventure.

Kelly Lael (’13) and Jenn Carlson (’10), who have busy professional lives, took on the responsibility of logistics for this expedition.

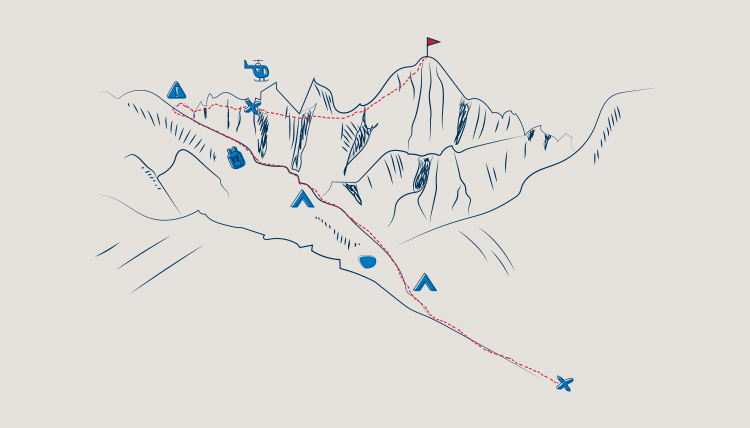

MOMENTS ON THE MAP

- The plan: The Zags will spend night one at 10,000 feet for altitude acclimation and night two at 12,000 feet to allow for an early-morning ascent of the 1,200-foot icy chute. Some set out at 2 a.m. while the snow is still firm; others start later.

- Foreshadowing of trouble: Zag climbers find a trio of hikers from another university who appear questionably prepared in jeans and summer boots; one is lugging a heavy rock.

- Divine intervention: The first team notices a small day pack sitting on the snowfield with no one else in sight. They call out, no one answers; they continue their journey.

- Finding trouble: One team reaches Trail Crest and finds two members of the trio encountered the day before. The two young men have spent the night with no water, extra clothing or food; their third companion is stranded on a 14,000-foot ledge, injured.

- The rescue: Part of the Gonzaga team cares for a hiker in advanced stages of hypothermia; other members set out to find the stranded man with the rock. Ultimately, National Forest rangers and a helicopter crew evacuate him, while GU and Air Force climbers assist the other two hikers down to safety.

- Summit: Having established contact with the injured hiker, and arrangements made for helivac, the six Zags who charged forward to deliver aid are instructed to continue on toward the summit.

- The lessons: Participants view courageous leadership from a whole new vantage point. Their reflections, next.

CLIMBER REFLECTIONS

A Saga of Suffering and Service

Reflecting on this incident, I feel gratitude: First, to my Gonzaga colleagues, who exhibited true servant leadership by sharing clothing, food, drink and aid to those in need; second, for my training as a Boy Scout in North Idaho and later as an adult in Utah. “Be Prepared” became less of a motto and more of a saving grace. Finally, I am grateful for the cooperation of those we assisted. Having the humility to receive help, to admit mistakes and learn from them, is another important trait of leaders.

There were two distinct leadership styles juxtaposed during the incident on Mount Whitney. First, the person who had to be airlifted was a somewhat experienced outdoors person, but exhibited an inflated perception of his own abilities and seemed unaware of the limitations of his companions. Second, the leader in the Air Force duo also climbing that day was very aware of the limitations of his hiking companion and made sure they had appropriate supplies. The leader of the trio in danger had suggested that his companions leave their packs behind to make the climb up the chute easier. He was intent on carrying a rock from the base of the mountain to the summit and back, and add it to his collection. Later, he confessed his pride and acknowledged this experience as a life-defining moment. In contrast, the Air Force pilot decided not to expose his companion to unnecessary risk: When informed of softened snow conditions, he informed his friend, “We will not be summiting today.”

Mount Whitney is a metaphor for the everyday challenges of life which we all experience. Resilience, hardiness, an encouraging heart, humility and serving others are traits I hope we will use in all aspects of life whatever mountains we might climb, either in our professional roles or personal lives.

Bruce R. Hough (’18)

President Emeritus, Nutraceutical Corp. | Park City, Utah

Keep Going

Sometimes when life is hard, I take on something harder. Perhaps this is the only clear explanation for why I signed up to climb Mount Whitney. My life is not about accomplishments, achievements or that hollow idea of a bucket list, it’s about finding my internal strength when I need it.

When I was asked to be a team leader, I spent time in discernment. I know leading a team of peers is a privilege. I committed to being present, to accept them where they are and to encourage community.

On the mountain, I carried a small piece of granite from the quarry that made the WWII memorial in our nation’s capital, to honor the strength and courage of those who faced great uncertainties. By keeping others in my awareness, I had almost no room to let doubt creep in.

Despite the physical demands of the climb, my experience left me renewed. Our Zags reminded me that GU’s Organizational Leadership program attracts and develops a unique group of people. It’s a tremendous gift to have this community to come back to for renewal.

I took almost no pictures, but the mountain is still a presence within me – a new strength I can draw on.

Kelly Lael (’13)

Public servant in the federal government | New England

The only female members of our alumni team, Kelly and Jenn, led us with resolute courage in volatile, unpredictable, complex and ambiguous alpine. In a landscape and climbing industry largely represented by masculine identities, their leadership enriched the journey, fostered team cohesion, and evoked joy in struggle.

Every Little Step

The jagged peaks soared as we pushed ourselves up shining fields of crunchy, white snow, the Southern California sky brilliant like sapphires. The images of this majestic landscape are burned into my mind. With each step, I was living a dream as the expedition photographer. The Organizational Leadership program had changed my life once already, and now it was happening again.

I captured videos of our progress and took stunning portraits against the immense backdrop. The view was breathtaking, and I was literally suffocating. (In the altitude of the Sierra Nevada, the oxygen level drops significantly. The chill of the air saps moisture, leaving you dehydrated.)

With exertion, we stayed warm, but in the shadow of the mountains, the temperature dropped drastically. We started counting out steps and rests. “Step… 2… 3… 4… 5… 6… 7… 8… 9…10… Rest… 2… 3… 4… 5…” We took longer breaks to eat energy-rich foods like trail mix and glucose gels. Small, deliberate decisions. We all make little decisions every day. There’s a chance that any

one of them can lead to either success or disaster. Go past or stop short. Continue with or without certain resources. In this way, mountain climbing and organizational leadership share a deep foundation and are rich with metaphors.

Effective change initiatives and mountain summits both provide a clear and compelling goal and vision of success. Preparation provides certainty of the skills required and necessary tools for the trip. You need a map for your journey and everyone needs to stick to the same trail, otherwise people get lost. You need a leader at the front looking toward the distance, but everyone needs to focus on just one step after another to maintain progress. The list goes on, but I like to cap it with this final rule: Not everyone has to make the summit, but it is required that we all make it back down. There is absolutely no reason to leave someone on the “mountain” in your organization.

Mount Whitney reaffirmed my purpose, passion and principles. Not only did I reconnect with old friends and challenge myself beyond known limits, I was inspired to continue building the concepts and practice of adventure-based leadership development, a new journey to document the leadership lessons discovered on the mountain.

Kyle Denton (’18)

Department of Defense | Gig Harbor, Wash.

Smallness in the Vastness

My lasting connection with mountains started in a Gonzaga course called Leadership and Hardiness – a summer course that involves climbing Mount Adams in Washington. As a Midwesterner, I had no concept of mountains, so I committed without truly understanding the journey. It was the hardest physical undertaking in my life, and I was never the same afterward.

Each year, I join other volunteers to support (Adrian Popa) and the Leadership and Hardiness community through successful summits and through climbs turned around by weather and illness. I have learned so much from each of them. With Mount Whitney, Adrian developed something different, with suggested readings as primers for curious exploration and self-reflection.

My trip memories include the extra day with dynamic Bruce Hough reconnoitering and visiting the National Park at Manzanar; camping at frozen Lone Pine Lake, watching most of our team ascend under headlamp; boiling and then pumping water the evening before the summit attempt; Kelly summiting; glissading in soft, dry powder; the Sikorsky overhead and thoughts of our troops in Afghanistan; my smallness and the insignificance of my daily concerns in the vastness of nature; and the warmth, generosity, care and concern my fellow Gonzaga climbers put into practice for those in real need.

With each set of mountain experiences there are common threads: the uniqueness of the time, place, happenings and community in the moment – singular and fragile; memorable and lost; insignificant and impactful; visual and auditory. No trace I was there and lasting memories that guide me.

Michael Symonanis (’13)

Director, Global Container Logistics

Louis Dreyfus Co. | Memphis, Tenn.

A Four-Point Message

Leadership takes on many forms, especially at 14,000 feet. Here are some from Mount Whitney:

Expressing Vulnerability. It’s OK to feel nervous when trying new things; this is acknowledgement of what’s at stake. Overconfidence or disregard of risks can be detrimental, and as we encountered, potentially life-threatening.

Adaptability. On the mountain, things can transform quickly. Weather changes, timelines shift, injuries happen. Adapting on the fly while maintaining a level head is important. As a leader, you have two options when obstacles arise: Keep your cool or freak out. Only one of these allows you to make the best decisions.

Preparation. The level of preparation varied greatly within our group, and a delicate balance emerged. Effective leadership is knowing when to tap into the resources of the overprepared. And when redistribution of weight is needed. Similar applications can be made in the workplace.

Leading from the front or back. Leading from the front allows you to set the pace and blaze the trail. Leading from the back allows you to identify those who are struggling, change course (if needed), and ensure no one is left behind. Having strong leaders in front gives a group confidence; having strong leadership to bring up the rear provides security. Practice doing both.

On Mount Whitney I witnessed how leadership can be enthusiastic, complimentary, patient, conflicting, even beautifully flawed. Such experiences provide the ideal environment to experience, learn and even practice different leadership styles. Adversity offers gateways to identify strengths and become a more well-rounded person.

Trevor Airey (’16)

National Account Manager, Philips | Renton, Wash.

Take the Leadership Dive

The School of Leadership Studies includes these programs for professionals considering their next career step. Each has online learning components with short periods of on-campus experiences and opportunities for immersions in other locations.

- Certificate, Women Lead

- M.A., Organizational Leadership

- M.A., Communications & Leadership

- Ph.D., Leadership Studies

- Academics

- Alumni

- School of Leadership Studies

- Graduate Admissions

- Master of Arts in Communication and Leadership

- Master of Arts in Organizational Leadership

- Gonzaga Magazine