Letter of the Law

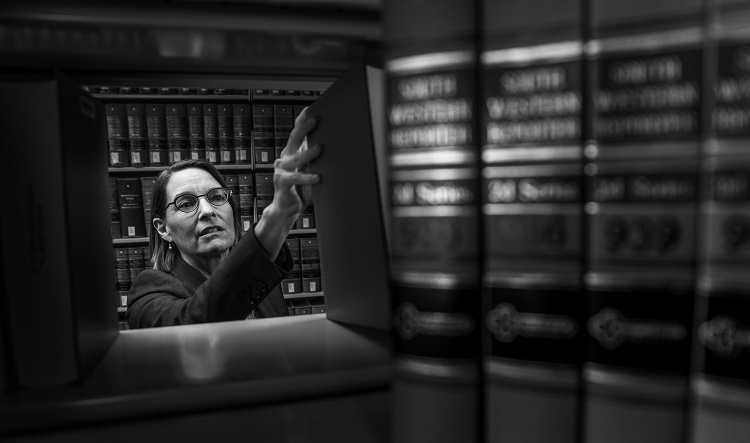

The connection between property law and the plight of refugees – for most of us – is little more than a dotted line on an exercise in free association thinking. But for Megan Ballard, professor of law there is a thoughtful correlation – a clear movement from one to the other with touchstones of meaning and purpose.

Much of Ballard’s research and teaching has focused on property law – the rights of owners, the limits of protection. Eight or nine years ago, she began to cast those topics into international light, looking at the limits of property owners forcibly displaced from their homes in the horrors of war or ethnic turmoil.

“How do people prove that this piece of land is the farm they were forced to leave? What evidence would there be?” Ballard began to ask. “How do you restore rights after a conflict in the face of such daunting hurdles?”

Those questions led her deep into research, first in the countries of Georgia and Colombia, and soon, to Jordan. But between those international field research trips, Ballard connected with Spokane refugee services to make her research personal.

“Some of our new residents have lived for 10 years in a refugee camp. They don’t know that in the U.S. you can’t leave a child in a car in a parking lot for 10 minutes,” Ballard says. “Refugees can be removed from the U.S. if they violate certain laws. That triggered an idea to help them understand more about law.”

She started volunteering for Refugee Connections Spokane (RCS), creating a curriculum to teach refugees about their legal rights and how not to endanger their status, and partnering with Community Colleges of Spokane to present workshops translated into several languages. As a scholar, she augmented those efforts with a piece published by the University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law. As a professor, she guided law students and lawyers in helping to provide essential information to refugees. As a volunteer, she also helped with World Refugee Day in Spokane, an annual celebration of refugees taking their oaths as legal citizens of the United States.

During her workshops on law, Ballard says that, without doubt, the questions refugees had about family norms and expectations were the most interesting.

“While our conversations varied based on the country and culture of origin, many newcomers are not only concerned about legal rules, but also about how families in America operate,” Ballard explains. “Are the parents responsible if the child does something wrong? How old should my child be before I can leave him alone? What are the appropriate ways of disciplining children?”

Another, touchier topic was the parameters of domestic violence, especially for those coming from cultures where women and men had very different roles. “We approached the subject by saying, ‘You might not agree with the rules. But this is the status of the law in the United States’,” Ballard says.

Bringing lawyers, judges, law faculty and students, and community college language instructors together to help people uprooted from their homelands gain footing in their new country was enriching, she says.

“It was a pretty awesome thing.”

Fulbright Scholar: Resettling Refugees

“How do we welcome newcomers to society? Are we simply admitting refugees to respond to international and domestic pressure, or are we trying to create citizens who will engage in civil society?” asks Megan Ballard. “This is an idea I kept coming back to.”

Ballard pitched those questions to the Fulbright Scholar Program and in 2018 received a grant to continue studying refugee resettlement programs. Her Fulbright-funded stay in Jordan this fall will put her face to face with refugees who have been accepted for resettlement in North America and are receiving an orientation to either the United States or Canada. Ballard will compare how the countries differ in presenting law and legal culture in welcoming newcomers through orientation programs.

Before she was on the ground in Jordan, Ballard already had an idea of some of the differences in the two orientation curricula. Take, for example, the mere names of the programs offered to refugees: Canada calls the course a “pre-departure orientation” whereas the United States calls it “cultural orientation.”

Ballard explains. “The Canadian orientation seems to value multiculturalism. It says, ‘We want refugees to maintain their cultural identity but adopt a Canadian identity also.’ The law is a small piece of both orientation programs. In Canada, law seems to be framed largely as a tool of empowerment.”

In the U.S. version, the message is different. “We want people to understand our culture and generally conform to it. The curriculum seems to present law mostly as a way of restricting behavior,” Ballard says.

As she dusts off her rudimentary Arabic and packs for the Middle East, Ballard hopes her research eventually will hold up a mirror and help us see more clearly how we introduce newcomers to law and legal culture. Ultimately, that will impact refugees’ resettlement, integration and civic participation in their new homes.

Read more from our "Welcoming the Stranger" series:

Scott Starbuck, Religious Studies, pedaled 426 miles to raise funds for refugee services

Shannon Dunn, Religious Studies, befriends refugee families new to Spokane

- Academics

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Service & Community Impact

- School of Law

- Gonzaga Lawyer