Researchers Find 15- to 16-Million-Year-Old Squirrel Fossil at Clarkia, Idaho Site

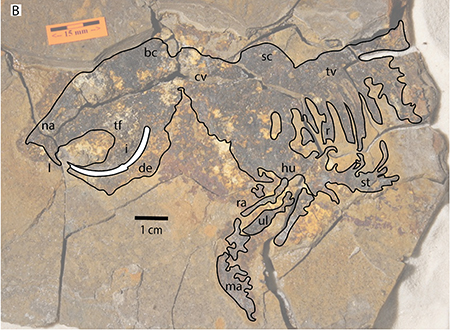

(Above) The tree squirrel fossil found at the Clarkia Lagerstätte site. Photo by Bill Richards

By Amy Shellenberger

For Gonzaga News Service

Crack open a rock in the Clarkia Lagerstätte fossil site near Clarkia, Idaho, and you’re likely to find a well-preserved leaf from the middle of the Miocene Epoch 15 to 16 million years ago, preserved so well that you may even briefly see some of the original colors before they oxidize to black.

Crack open another rock and you could be lucky enough to find a tree squirrel fossil from that same period. That’s what happened when a group of students led by North Idaho College Professor Bill Richards, Ph.D., embarked on a research trip in search of fish fossils at the north end of the Kienbaum family racetrack in 2009.

The squirrel is the first four-legged animal scientists have uncovered in Clarkia, and it provides an important clue in the history of an area rich in leaf fossils and ancient biological molecules.

“It’s not out of the ordinary to find sites with really well-preserved leaves, but it’s almost completely unheard of to have sites that actually preserve DNA, proteins, things like that,” says paleobiologist John Orcutt, Ph.D., Gonzaga University biology lecturer.

The part of the skeleton the team found is remarkably detailed. “To actually have the whole outline of the body like that is very unusual,” says Orcutt. “And now we’ve added an entirely new group of animals to an important site, which gives us a better idea of what that ecosystem looked like.

“Clarkia is only one data point, but it’s an important one because of the level of detail it preserves. It allows us to ask questions about the ecosystem variables of this site in more detail than you can in a lot of other areas, because you can look at the microstructure of the leaves all the way down to the molecules in them. Now we have a better idea of what kind of animals lived there, too.”

Though the squirrel is likely a newly discovered species, the team is also interested in how it fit into its ecosystem, how those ecosystems changed over time, and what caused the changes. The finding is especially relevant because the middle of the Miocene Epoch had roughly the same degree of climate warming scientists are predicting by next century: 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit).

As Orcutt points out, though, there’s a big difference between that kind of change over several million years versus several decades. “Anything we can do to give us a better idea of what this really important ancient ecosystem looked like during this period of global warming potentially helps us better understand how things were changing. Ideally that gives us a better idea of how things could change as our climate warms now.”

The fossil will ultimately be housed at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle. To read the complete article published in PeerJ, visit https://peerj.com/articles/4880/.