Boldness & Confidence: Lessons at Women Lead

Presented by Gonzaga’s School of Leadership Studies, the 2018 Women Lead conference featured a bit of science, the truth of case studies, insights and statistics, plenty of laughter, and even a little air guitar. More than 250 attendees represented nearly 60 regional organizations. Following are snippets from keynote speakers.

By Kate Vanskike-Bunch

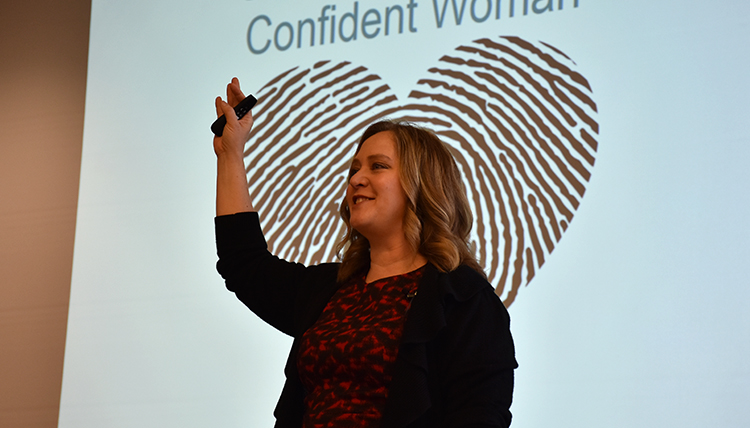

The Confidence Marker

There is a psychological predisposition – a genetic marker – for confidence, and about half of us are born with it, says Deanna Davis, Ph.D., an author and speaker with a background in public health and leadership.

In Latin, “confidence” means faith, to trust, firmly trusting, bold, and in psychology, it’s defined as a belief in the ability to succeed. “The unifying theme here is believing,” says Davis. And, “The more we pay attention to confidence, the more we act on it.”

That, Davis says, means women have to stop diminishing the work they do, whatever it is.

“Don’t apologize for being a mom who loves her child. Don’t apologize for caring. Those things make us strong in the home, in the school, in the workplace, in the community.”

Further, she says, women need to stop apologizing for their knowledge and the influence they can have. Studies show that men consistently overestimate their abilities and their performance, while women consistently underestimate both.

One key way for women to show and improve their confidence? The power stance, Davis suggests – the universal victory sign that most often is used by men. Taking up more space is a common practice of men, whereas women tend to try to make themselves smaller. “Women who are confident show it in a powerful gesture, and it kicks us into more boldness,” Davis adds. “Those expansive and expressive stances fire the neurons of confidence.”

Learn It: The 4 A’s

Assume the pose

Access the memory

Ask for what you need

Act (think, believe, do)

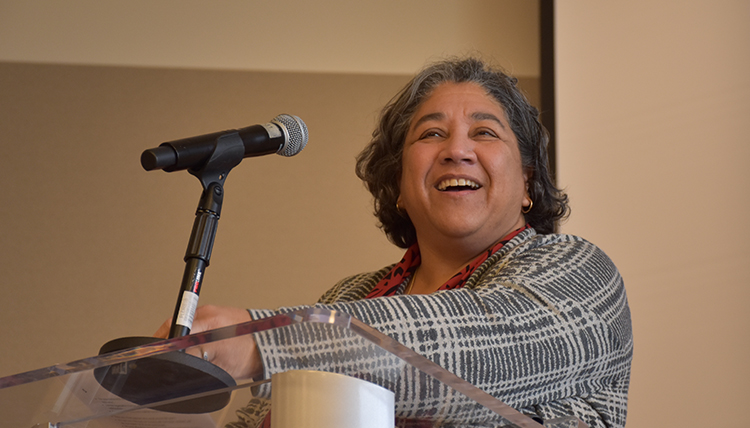

The Boldness to Ask

Liz Baxter, MPH, came from a family of Danish slaves who deeply valued education … of boys. Of nine children in her mother’s family, eight female children provided the way for their one brother to go to school.

Her mother grew out of that experience with the expectation that if you don’t believe something is fair, or you don’t understand, or you feel you were wronged, you must simply ask about it. “You might actually fix something for someone else,” is the lesson Baxter learned from her.

“Take your nervousness and put a voice to it,” Baxter advises. “What’s the worst that can happen?”

It’s something she has practiced in her personal life as well as professional roles. In the 1980s, Baxter and her partner, Nancy, wanted to apply for foster care and eventually adopt. It was three years before the couple had a home study, five years before adoption was final. But when the department of vital statistics asked for the name of the father on the birth certificate, all it took was one call.

“We simply asked, ‘What’s the possibility of having the form ask who’s the parent and who’s the parent rather than mother and father?’ Two weeks later, we received a birth certificate that listed our names next to ‘parent’ and ‘parent.’ Changing the form wouldn’t have happened if we hadn’t asked.”

Baxter scoffs at the familiar quote, “When one door closes, look for the window.” She quips, “Or … you can open the door. That’s how doors work.”

Another keynote speaker was Sister Helen Prejean, author of “Dead Man Walking.” Read more here.