All God's Children

Story by Marny Lombard / Photos by Rajah Bose

On a gray Friday morning at St. Madeleine Sophie School, a student named Gracie balances concentration and caution as she comes down the steps. Gracie wears a broad, padded belt and shadowing her, both hands grasping the belt, is Martine Romero (’00). At the bottom of the stairs, Gracie grabs her walker and bounces off to homeroom. A second-grader with a ponytail, a pink jacket, a damaged heart and mild cerebral palsy, she is not unusual at St. Madeleine Sophie.

Just over half the teachers here are Gonzaga alumni. Some knew they wanted to work here after hearing Principal Dan Sherman as a guest speaker at Gonzaga’s School of Education. From his descriptions, they knew they would find a community of the heart. This school, with 200 students in pre-K to eighth grade, opened 10 years ago. St. Madeleine Sophie’s mission is to educate and make community with all of God’s children, no matter their economic, ethnic or academic needs.

Forty percent of St. Madeleine Sophie students require individualized education plans. The school accepts all children, those with Down syndrome, those who are somewhere on the autism spectrum, even those whom other schools have shied away from. You will find highly gifted students, non-native English speakers, including a few students each year who come from South Korea and stay just a year or two. The students seem to absorb the empathy that their teachers model. They cluster around Gracie and others who might need a steadying hand. Every child plays together during outdoor gym. Every child is invited to birthday parties.

Last summer, this model of including all students earned the school national attention. Principal Sherman won the Edward Shaughnessy III All God’s Children Inclusion Award. Ordinarily for this award, the judges’ decisions are closely called. But Sherman and the work he leads at St. Madeleine captured every single vote.

Sherman credits the teachers from Gonzaga for much of the school’s success. “They understand Catholic teaching in social justice. They know how to reach out to our students. Each one is an excellent teacher with an enormous heart,” he says. The first place he looks for new teachers is Gonzaga’s School of Education.

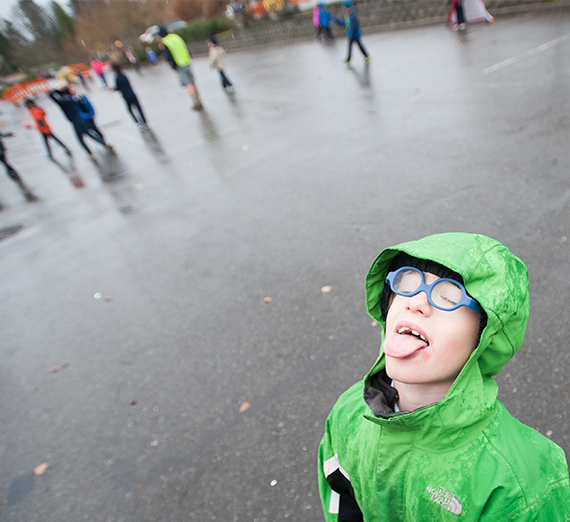

At lunch, Romero sits next to Calvin Bertsch. You can’t miss Calvin, with startlingly blue glasses and an owlish gaze. He munches on carrot sticks and watches the lunchroom hubbub, while Romero injects a dose of extra nutrition into the feeding tube that ports into Calvin’s tummy. He is a medically fragile student, but he’s happy to pull his shirt up to show visitors the “button” on his feeding tube. His parents found St. Madeleine Sophie through recommendations from Calvin’s doctors at Seattle’s Children’s Hospital. He’s not the only student to arrive by this path.

“We just wanted a place where our three kids could be all together,” says Tricia Bertsch, Calvin’s mother. “With his mitochondrial disease, one school turned him away as a liability. We came to visit on a Friday, and on Monday all three kids were enrolled.” Calvin is in and out of the hospital several times each year. His extra nutritional needs mean that he must be tube-fed supplements twice a day.

“I said, ‘We’ve never done this before, but we can try,’” Romero recalls. She learned from Tricia how to do his supplemental feedings, and now is earning her master’s in special education through a full scholarship to the University of Notre Dame. Her position as director of inclusion gives her oversight of the extra planning for many of the students.

“The moment we walked in here,” says Calvin’s mom, “we felt like we were home. That is what it comes down to.”

THE RULES OF INCLUSION

By Rajah Bose

I was in the entourage of a 6-year-old.

Gracie had news that every kid at school wanted to hear, or so it seemed. They were following her across campus, a bouncing battering ram of pigtails and batman backpacks, as she spread the word. In her bag she carried an ultrasound picture of her brother-to-be. She found the principal who knelt beside her to get a better look at the black and white photocopy.

“Baby,” Gracie said definitively, and waited for him to match her joy. When he did, her work was done.

She quickly put the picture back into her bag that dangled from her walker and made her way toward her classroom. The wheels spun quickly as she almost skipped across the campus. I could barely keep up with my tripod and video camera.

I was at St. Madeleine Sophie School in Bellevue, Washington to photograph and document the work that Gonzaga alumni were doing at this school founded on the idea of inclusion.

As Gracie approached the classroom, another student ran from behind me to open the door for her. She slipped past and disappeared into the room where the little chairs and desks were waiting.

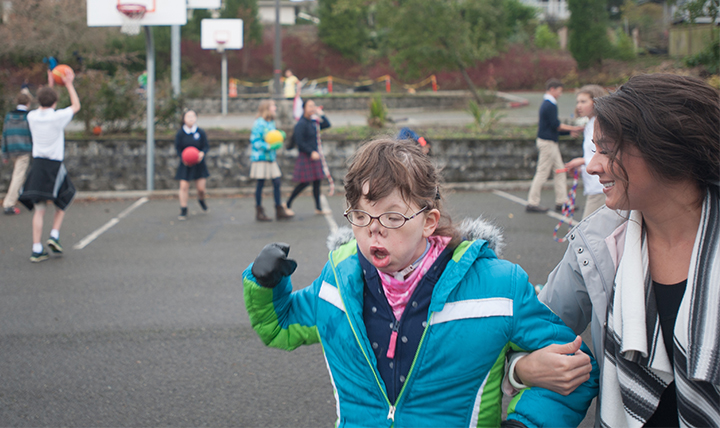

At recess I lagged behind a group of young teen girls who were strung together arm-in-arm as they strode across the parking lot that the school uses as a playground. In the middle was Kenya, who wore a bright pink raincoat and a wide smile which seemed to hold her eyes closed.

They gathered under a tree to chat about the usual things — their teachers, homework, what game they wanted to play. But not about boys, not yet (though that may have had something to do with me looming nearby). They asked Kenya what she wanted to do and she nodded along as the group went to retrieve jumpropes.

That afternoon in the classroom, Julie Grace worked with her classroom aide on flashcards alongside an anxious, dark-haired boy named Noah. Both were buried in their work, she with a reading project and he on his handwriting. He kept looking over his shoulder at her to see what she was up to. Both were distracted by one another.

Once he had finished tracing the lines with his stubby pencil, he stood up to chat with his friend. He communicated with Julie Grace through the monitor attached to her wheelchair. As they looked at items on the screen, the computer interpreted what they were looking at and said the answer in a robotic childlike voice.

I watched as Noah took Julie Grace’s hand in his and held a paper cutout he had made to his nose. He was hoping to get a laugh from her. I couldn’t tell if he did. They were hand in hand for a few moments before she yanked hers away. This was elementary school after all.

Throughout the school, students of all abilities were in classes together, working and playing in the same group. All students learned with one another, even those with different abilities. Especially those with different abilities.

When I was in school we also believed in inclusion. We told Billy, who we knew didn’t quite know better, that he should run across the gym and dance for the girls. He would soon be running back toward us with his shirt off. The girls would scream, and we would laugh, and then he would laugh and feel included.

That was inclusion.

Billy was our age, maybe older, but had limitations to his comprehension. We viewed ourselves as separate — we were one, Billy was the other. We would have never let anything bad happen to Billy, but we mostly just watched out for ourselves.

Billy spent the rest of his time at school in a separate classroom, a place they called Special Ed. I took algebra and tried to figure out Shakespeare. The only times we saw one another were during physical education and lunch.

Billy liked the attention and entertained us without prodding. He ran onto the empty floor during school assemblies to dance, thrusting his pelvis around as the students in the bleachers laughed. During lunch, he walked around and talked to everyone. Sometimes he stole some fries and then he took his shirt off and whirled it around his head. He knew he could make people laugh by doing something they couldn’t.

Still Learning

Many years later, I still find it difficult to create an understanding and comfortable space between myself and someone who is different. A teacher at St. Madeleine’s explained to me that inclusion is not necessarily something we are born with — it must be taught. St. Madeleine’s does that every day by modeling the behavior in teachers and encouraging it between students. They don’t just talk about the idea of inclusivity, they bring the students together in one classroom to work and learn together.

It wasn’t by mistake that the students ran ahead of Gracie to open the door for her, or jumped rope with Kenya, or took a break from their classwork to chat with Julie Grace. All students were expected to learn with the class. Aides were available to help with special needs, but much of the learning was done among the students while nobody else was watching.

In some way, the same was true for my crowd and Billy. When I even considered attempting something against the rules, it seemed that teachers were around every corner, watching. But with Billy, we were an island from their suspicion. Perhaps they thought we were watching out for him, taking Billy under our wing, giving him some lessons on life. Really, it was the other way around.

I can credit Billy with teaching me that. The same is true with Gracie, Kenya and Julie Grace for all the students at St. Madeleine’s. In just one afternoon while they were busy jumping rope and tracing their alphabet letters, they showed me there was still so much left to learn.